Artists have been communicating ideas around sex and love for centuries—we’re looking at you, you saucy ancient Greeks, randy Romans and erotic Egyptians!—but for significant chunks of history, society demanded an altogether more subtle artistic approach to amour.

As a result, a cipher of symbols and codes all relating to sex, desire and forbidden love sprang up, allowing artists to reflect and reveal the passions—and libidos—of their time in a way that was masked in decorum. With that in mind, read up on our 101 of art history’s in-jokes and iconography and make your next trip to an art museum all the more arousing…

Ripe & Ribald in the Renaissance

Thanks to today’s visual language of emojis, no longer is an eggplant just an eggplant, a peach just a peach. But even before the dawn of social media, artists of yesteryear incorporated fruit and veg into their work for similarly suggestive ends.

Case in point, Niccolò Frangipane’s masterpiece of 1597, ‘Allegory of Autumn.’ Showing a cheeky satyr (fun-loving woodland creatures of Greek mythology), the scene is loaded with not-so-subtle clues as to the nature of the dozing young man’s lusty dreams. In particular, the satyr’s fingering of a suggestively split melon, his firm grasp around what looks to be either an eggplant or a sausage, right next to a smattering of cherries…

Not all Renaissance sex scenes were rooted in mythology—artists like Johannes Vermeer found ways to imbue a dash of desire into this seemingly staid depiction of a piano lesson.

The formality and so very respectable distance between the two belies a palpable sexual tension.

Are we meant to connect the sensuous curves of the cello to those hidden beneath the folds of the woman’s dress? Does the pitcher of wine imply the possibility of a drunken casting aside of inhibitions? Maybe, but the biggest giveaway is the woman’s longing gaze towards her dashing tutor, captured in the mirror above the piano.

Lusty Locks: The Ravishing Pre-Raphaelites

Beware of her fair hair, for she excells

All women in the magic of her locks,

And when she twines them round a young man’s neck

she will not ever set him free again.

Fast-forward to the Victorian era, and explicit depictions of sex and desire were still strictly off-limits for artists. Nonetheless, pre-Raphaelite painters continued to find ways to sneak sex into their work. At a time when women’s social role was uncompromising in its expectation of virtue, ‘fallen women’—those who had succumbed to seduction and sin—were held as cautionary exemplars of the dangers of skimping on morality.

But judging by the art of the time, these archetypal femmes fatales were dangerously alluring, sensationally sensual, and front and foremost in the minds of many a male artist. One need only look to Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s ravishing portrait of Lady Lilith, the first wife of Adam according to Judaic literature, to understand why.

In art, temptresses of the time shared several physical qualities, all modelled here by the lovely Lilith: exposed shoulders; a dangerous narcissism (she’s checking herself out in the mirror, see); and above all, masses of tousled, lustrous hair.

If flowing hair is a symbol of dangerously unbridled femininity and by extension, sexuality, what to make of John Everett Millais’ The Bridesmaid? Loaded with sex symbols and signifiers, this one is deceptively lustful.

The eagle-eyed will notice that the young woman is passing a piece of wedding cake through a ring. According to old English tradition, popping those consecrated cake crumbs under a pillow makes the sleeper dream of their future spouse. Orange blossom—a symbol of chastity—contrasts with not just the longing of her gaze, but also that gorgeous mane, another artistic indicator of simmering passions. Millais even throws in an upright and distinctly phallic salt shaker sexual for the complete expression of repressed desire.

Sex Symbols and Surrealism

Just as seemingly innocuous artworks can be a cover for undertones altogether more sexual, the opposite is also true. After all, by operating exclusively in the realm of the subjective, artists constantly run the risk of unintended meanings being piled onto their work, or of appropriation for a cause they themselves didn’t intend.

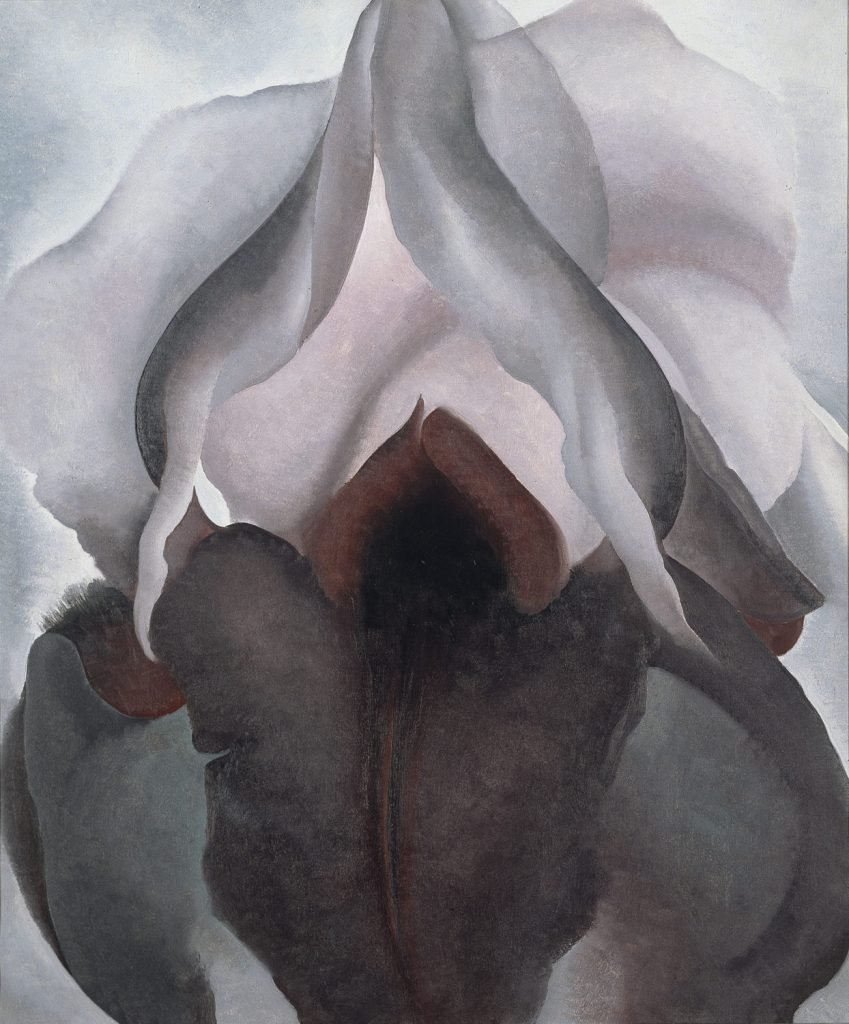

That’s exactly what happened to Georgia O’Keefe, best known for her close-up paintings of flowers that also happen to look a lot like vaginas. But while the artist herself vehemently denied the blooms-as-vulvas metaphor, the erotic interpretation persists to this day. The reading, incidentally, was pioneered by photographer Alfred Stieglitz who would go on to become O’Keefe’s husband. An early proponent of the tenet ‘sex sells,’ it was in promoting the artist’s work in 1919 that he first suggested the plausible but flawed analysis.

Around the same time, the Surrealists were embracing themes of sexual desire with gusto. The movement produces many an explicit artwork—we’re looking at you, Max Ernst—but also more cryptic offerings. Case in point, Méret Oppenheim’s delightfully absurd tea cup or Object (The Luncheon in Fur). Playing on crockery’s connotations of genteel refinement—is there anything more ladylike than sipping from a cup and saucer?!—and the female body, the work is a visual pun for cunnilingus. Get it?

Conclusion

When trying to spot the sexiest images, you might be tempted to head straight to the nude figures, but as the above examples show, even the tamest tableau can be hiding a few sly winks and nods—if you know where to look!

[related_article id=”9735″ size=”full” target=”_blank”]